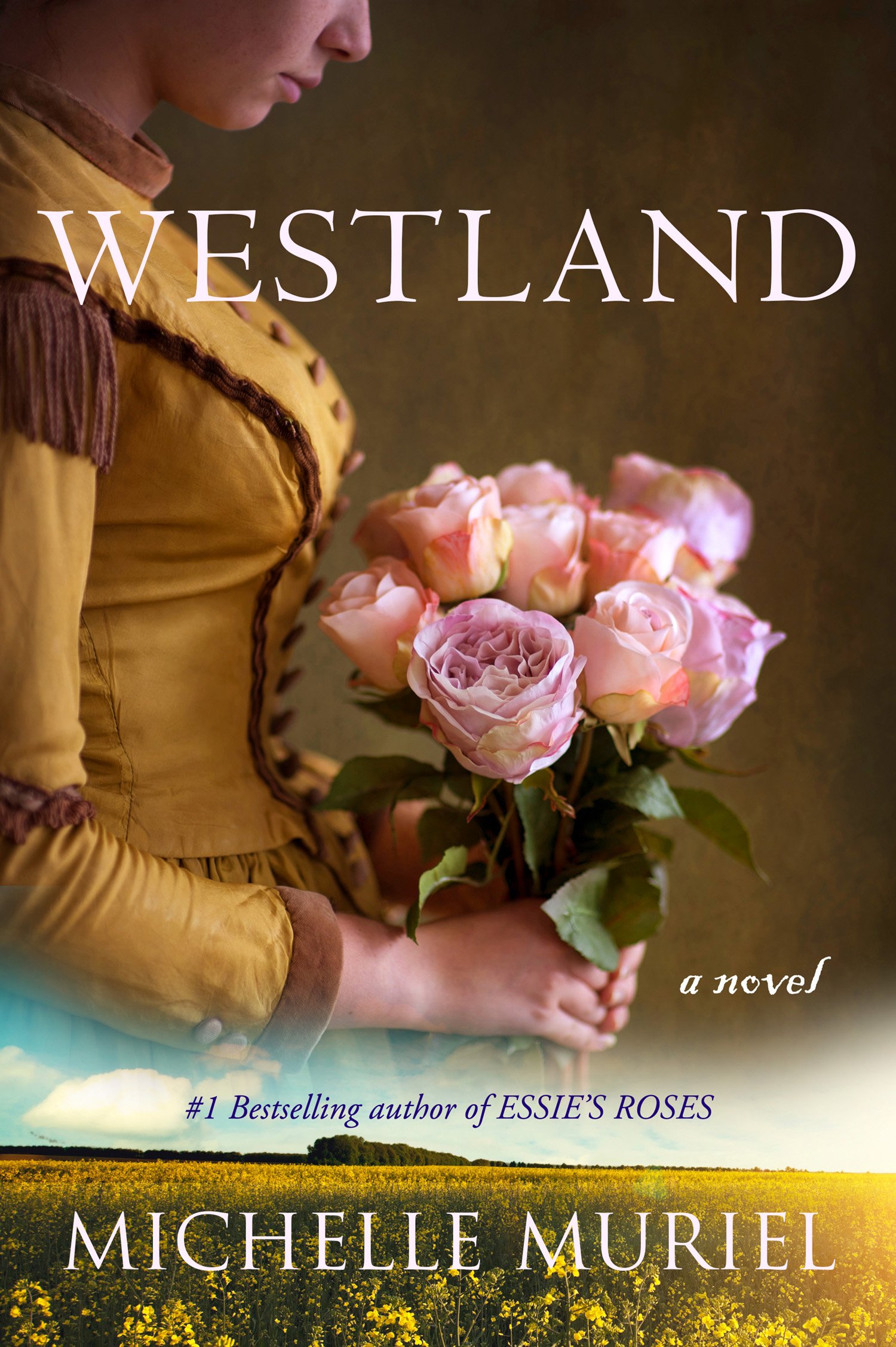

WESTLAND (Essie’s Roses Book 2)

by Michelle Muriel

EXCERPT

WESTLAND (Essie’s Roses Book 2) by Michelle Muriel

Format: Hardcover, Paperback, eBook

Genre: Historical Fiction, Literary Fiction

ISBN: 978-0-9909383-6-1 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-0-9909383-7-8 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-0-9909383-8-5 (eBook)

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

PART I

Prologue

KATIE

Alabama

Summer 1866

I held my breath, watching the flames from my bedroom window. A plume from my past rose above the trees, blacking my sunset. “Lord in Heaven, someone’s out there.” I glimpsed a figure in the shadows. Man? Woman?

Ghost.

I froze, clutching my chest, trying to breathe. Since my illness, I could not trust my mind to discern the sight real or imagined: a silhouette, tossing a torch, running into the forest.

Adrenaline replaced my frailty as I rushed to Essie’s garden. My legs failed me; I collapsed near its gate. Ash defiled the sweetness of rose perfume.

“Miss Katie,” Delly called after me. “Katie girl!”

Katie girl. Delly’s call transformed me from forty-five to four. Delly raised me during the early days of Daddy’s Westland when the small plantation grew more wildflowers than cotton. On her first day, Delly, a young black woman, marched up our porch steps, enamored with my golden hair. Mama’s “wild Katie” ran into Delly’s arms. Daddy laughed. Mama pried me away.

James and the men managed the brush fire behind Essie’s garden, and as flames curled toward the fence—a sprinkle of rain. Raindrops hadn’t splashed my cheeks since I was a girl. My tears flowed with them.

“Katie,” James called. He ran to me as I pictured a thousand times, dreaming of him when my life was not my own. For ten years, we lived as husband and wife. Ten years—a lifetime and vapor all at once. “Katie, you should be in bed. Do you want to catch your death?”

“I saw the fire and wasn’t thinking. I ran, James.”

“I don’t know how. You’re all heart, darlin’.”

I closed my eyes, falling into his arms.

“It’s over, Katie,” James promised. “The fire’s out. Let’s get you home.”

“I tried to stop her,” Delly said. She covered me with a quilt and pulled me toward the house. “Katie slip right away from me like she do when she a child.”

“Drought cause the brush fires this year is all, Miss Katie.” Bo, our gentle giant and protector, lumbered toward me with an unexpected smile. “You go on. We gonna fix it all.”

“I’m afraid the blight has stolen Essie’s roses faster than any fire,” I said.

Bo’s strong hands cradled mine. “But the roots still good. We save em, Miss Katie. We save em.”

That evening we all sat in the parlor, staring into the amber glow of a welcome fire.

“These be the only flames I fancy round Westland,” Delly mumbled.

James sat with me on the settee, nestled under our blanket. Delly and Bo quietly played cards—Bo in the parlor after all these years. My unlikely family, family they were. My daughter Evie and Essie Mae, an intelligent black child born at Westland I raised as my daughter, opened our first school for freed slaves in New York. They matured into women under my sister Lil’s guidance, making me proud.

“Do you think Evie and Essie Mae come home to stay now?” Delly asked, breaking the silence. “You want more tea, Katie?”

“I want our girls home,” I said, tired. I stared across the room at my mother’s empty settee. A flash of sewing lessons, debates with Father, tea with a dear friend. “James, the settee . . . I want Mr. Koontz to have it with Mama’s pink crystal vases and the lace doilies.”

Silence.

Delly couldn’t hide her sniffles. Bo cleared his throat, fidgeting to leave.

“Yes, Katie,” James whispered, scribbling it on my list of last wishes.

“Don’t like such talk.” Delly rose with a groan and poked at the fire. “No, ma’am. Now thunderclouds come a hovering in this room.”

James’s laugh strengthened my heart and put us at ease. “That’s just my pipe smoke, Delly.” James’s winks calmed Delly faster than any words.

A blur of pink silks and lemon pillows; I welcomed sleep. A tap on the door. A new maid Delly hired, Astra, entered the parlor appearing as a ghost. I hardly recognized her, but the past year, faces muddled in sight and memories. “Mr. James, trouble come,” Astra said, voice quivering. “They torched our barn. We save the horses, but Tom’s crazy stubborn battling the blaze. Such a sight, Miss Katie; men give up fighting that fire and watch it burn.”

“Go home, Astra. Bo will fetch Doc Jones,” James said, holding me tighter.

“Ain’t ya gonna help with the fire?” Astra asked, eyeing James, me. “Thirty men now.”

“If they’re watching the blaze, Astra, they gave up,” James said. “A new law rules in this valley now. Union soldiers will set this right.”

“But will they come?” Astra’s eyes peered into me, black, hollow. “Will they come?”

I turned away.

“I have my hands full putting out fires here.” James seldom raised his voice. “Astra, there’s nothing I can do now. We’ll take care of Tom and build him a new barn.”

Astra stood taller, scanning us, the exit. I focused on her hands, scarred and delicate, twisting her apron. “Indifference brought us slavery; it’s what’ll steal our homes now!”

“Enough.” I searched her eyes, the years and pain in them. “No one’s talking about indifference. The fire destroyed the barn. Or will you have me lose a husband for you too?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Astra whispered and scampered away.

“Don’t you go on feel bad bout not rushing over there, Mr. James,” Delly said. “Miss Katie has a right to say that, too. Why the neighbors go on thinking you the law in these parts?”

“Because James protected us during the war,” I said.

“In ways not fitting to speak on, hmm.” Delly rubbed my shoulders. I closed my eyes, absorbing the strength and peace through her hands. “That war’s over.”

“And a new one has started,” I said, surprising James. “Yes. It is time, James.”

Our crackling fire filled the silence. “It ends now.” James’s tender touch and whisper in my ear still caused a flurry of goosebumps on my arms. I relished his kiss. “I promise, Katie.”

“Time for Katie to rest. Take her, Mr. James,” Delly said with a peck to my forehead. “My china doll, you have sweet dreams tonight, sweet dreams.”

Peace blanketed our home, though a fire raged near Westland.

“Tom McCafferty’s all right,” Bo announced. “His pride’s hurt for not heeding the lookout or hiring them extra men.”

James carried me up to my room and tucked me into bed. “Katie, send for the girls.”

“My letter is ready.” It was the last loving night I spent with my husband before my sickness returned. I felt it, carefree in the rain, the heaviness in my chest, a fever. I rushed to Essie’s garden because I longed to feel strong and useful again. I wanted to save it, us, believe my life was not over but beginning. All the lost years returned. Lost love, found. I wanted to believe and dream among those roses. Ten years I savored the selfless love of a good man, ten years we fought day after day to keep Westland, keep me. And Essie’s roses helped me to dream again, helped all of us.

Westland, where its willows hold secrets, until the night air sweeps through their leaves, scattering them in the wind and into our ears . . . Evie, it’s time to come home.

1.

ESSIE MAE

New York City

October 1866

At the start of my journey, on a stop outside New York City, a little white girl boarded the train, reminding me of Evie. She eyed my potted rose, and as children do, stopped, stared, and plopped on the empty seat beside me, my chaperon soon to arrive.

The passengers did not gasp that a white girl stopped to speak to me, a black, young woman, nor did they wonder why the conductor had not moved me to a different car. I wore my finest blue dress, sapphire, as Evie’s night sky, a lavish gift from her aunt Lil and the yellow bonnet sprouting sky-blue feathers Miss Katie gave me on my birthday. My hair tucked in the soft waves Miss Katie adored, and a touch of peach blush and lip rouge, though Miss Katie claimed my creamy brown skin needed only a brisk walk for rosy beauty. But as I dabbed it on, the bit of makeup reminded me of Lil’s instruction at her long-ago school for ladies. “You said nothing of how to smooth crow’s-feet,” I whispered to my reflection in the sterling box mirror Evie sent me for my birthday. The woman’s portrait etched on top resembled Miss Katie. How we have all matured now.

“Miss, why do you hug that potted flower as a doll?” the little girl asked, wide-eyed.

Miss. I smiled to myself.

“Is it magical?” she asked, tugging my sleeve.

“You remind me of someone.” I laughed.

She scrunched her nose and tossed her blonde ringlets like Evie.

Her mother arrived. “Wren,” she called. “This is not your seat. Leave this woman alone.”

“But it’s my birthday,” Wren whined. “I’m seven now, and you said on our next trip, I may choose my seat.”

“Your daughter is charming. No bother,” I said. The fidgety girl tugged the fingertips of her white gloves. “Wren. What a glorious name. Are you a lilting songbird?”

Wren fluttered her lashes, aqua eyes pleading with her mother. “Oh, Mommy, but this nice lady was going to tell me a story about her magical flower.” She winked at me at last pulling off her gloves, and in an instant, the distracted child popped up at the call of the conductor, lured away by his musical whistle. “Mama, he’s giving out whistles.” She rushed to him.

“Stay close, Wren,” her mama called. “Children, they skip from one wonder to the next. We travel so much the conductor is an old family friend. He always watches over Wren.”

“She reminds me of someone. It’s hard to believe we were once that young and trusting.” I had meant to say curious, but it spilled out, my heart envying Wren’s innocence and radiance.

“Curious,” the woman echoed for me, watching her daughter show off to admirers. The conductor, distracted from his duties, taught Wren how to make her whistle sing. “I have seen you,” the woman said to me, smiling. “I’m Abigail Fitzpatrick. You don’t remember me.”

“Pleasure,” I said, relieved my defenses down. I nodded and shook her lavender-gloved hand. She caught herself, slipped off her gloves, and offered her delicate handshake. A flush washed over me as I gazed into her eager eyes, trying to recall our meeting. We managed the awkwardness, admiring her daughter swaying in her sun-soaked spotlight. I had imagined Abigail would grab Wren and complain about me to the conductor, but then, I have learned to believe first in the goodness of people; that most white folks were not like the ones who hurt me.

“My husband and I saw you speak at the Hayden Theater in New York. Exquisite, dear. We contributed to your school.” She removed her wide plum hat, fluffing her orange curls.

“Yes. Abigail! Of course. We bought many books with your generous donation. You are gracious, but we could hardly call the Hayden a theater. A river town’s hall perhaps, arranged with two rows of chinoiserie armchairs.” We chuckled.

“No. You spoke with such passion. It must be difficult keeping track of your admirers.”

“I have not given a speech in months and moved outside the city, to Piermont, to open a small school. I help a sweet elderly couple at their inn and cultivate flowers on their strawberry farm. They indulge my study of roses. I should say they help me.”

“The Morgans and their inn are staples in Piermont. Now I know why their courtyard garden appears lush and vibrant. Haley never could keep roses. They’re lucky to find you.”

“I sometimes lecture at Haddock’s Hall. The bustle of the city no longer thrills me.” My cheeks burned, speaking about myself.

“Cape May by steamboat in the evening during the season, delicious.”

“I’m entirely too busy to visit Cape May,” I said in jest. Evie would have laughed at the British accent I slipped, a ruse Evie performed during our stay in London, hidden from the war.

“How are Sam and Haley Morgan? Their strawberry festival was grand this year.”

I pictured the plump, juicy berries waiting for Haley’s hands to whip them into sugary concoctions—their sad faces as I waved goodbye. “Dear friends,” I said. “The festival is my favorite time of year, but I miss another quiet escape. Pleasure seeing you again, Abigail.” I was eager to rest and dream of my days on the strawberry farm, away from my roses and home.

Abigail remained, eyeing her daughter and rummaging in her handbag.

A man squeezed by, thumping Abigail with his satchel. “Pardon.”

“I should take my seat,” Abigail said. “But we are going nowhere fast. This train is always late. Where’s your husband, Thomas?” Her eyes twinkled, anticipating gossip.

I fanned my blush. “We are not married . . . friends.”

“I’ve misunderstood. My husband has eyed Thomas for politics.”

“It may be the other way around.” I inspected a leaf on my rose, restless to sit alone.

“Forgive me. I’m an anxious chatterbox before the train departs. My card. We’re returning to Mobile.”

“Alabama as well.” I rose, searching down the aisle for my late escort.

“My husband said many Southerners opposed to slavery left the South after the war for good. Others make trouble for those sympathizers who stay.”

Sympathizer. I despised the word, not for what it meant, but the hiss when whispered in disdain by those waiting in the shadows to snuff out its true meaning’s light. “Rebels are the failed leaders of the war bent on destruction of blacks and white Southern sympathizers and Union supporters. They are the enemy of freedom.”

“Yes. Yet you return?”

“For a special reason.” I shook off my memories, gazing out my window. A husband kissed his wife and children goodbye. He presented his pink peonies, making her sob. “Oh, red roses and white jasmine represent sweet love, peonies bashfulness.”

Abigail sighed as the couple embraced. “Peonies also mean romance, dear. Bah, I don’t believe in the language of flowers as I once did as a young girl in love.”

“At my school, I arrange a bouquet for my students, former slaves, every week. My favorite bouquet is one of pink roses for boldness, a sprig of mint: virtue, yellow tulips: hopeless love, and a stalk of willow . . .”

“For freedom.”

“Yes,” I said, surprised she knew the willow’s meaning. “I am sentimental, but the language of flowers saved me, Abigail.”

“And you have made me fall in love with the romantic code all over again.” Abigail looked at me fondly and handed me a violet from a posy in her satchel. “Faithfulness, I believe.”

“I teach my students beyond reading and writing, but navigating life’s hardships, planting hope, watering their faith, so that despite deluge or drought, something beautiful will blossom inside each one.”

“My dear, you teach something greater: curiosity. I dare say curiosity saved you, a curiosity to live beyond your station.”

“To live period.” I hadn’t meant to shame her, but I also hadn’t planned on engaging in a conversation on life and love, in no mood for the talk of either. I wanted to sit at my window, quiet, counting the hours until I saw Evie, Delly, Bo, James . . . and Miss Katie again.

Abigail waved to Wren. “I’m no speechmaker. My husband warns me not to discuss subjects I don’t understand.”

I chuckled. “How can we learn if we never discuss them?”

“Agreed. Perhaps women will lend our voices to politics someday.”

“We are. We shall.”

Abigail summoned Wren. “I hope you’ll call on me should you visit Mobile.” Wren returned, pushing her gloves into her mother’s hands, showing off her new whistle. “I’ll take that.” Abigail stuffed the noisemaker into her bag.

“Mommy, the conductor said, the train won’t leave for a long time. They’re fixing something or making more steam. I don’t remember.”

“We await the queen of this locomotive.” Abigail laughed. “Katy Dale, opera star and owner of a luxurious car furnished with red velvet seats, walnut paneling, and a bed covered in emerald silk.” Abigail relished her gossip.

I smiled a “Katy” traveled with me.

“Mommy, may I please stay to hear this lady’s story?” Wren asked.

“My manners,” I said, a blush prickling my cheeks. “Essie. My name is Essie Mae. Wren, what story?”

Abigail searched out my window. “My husband waits to see us off. He’s in politics and stays behind on business.” Wren tugged at her mother’s dress. The yellow satin skirt reminded me of a ball gown Miss Katie fancied, black embroidery and mother-of-pearl buttons. I looked out my window, picturing Katie waltzing with James in the moonlight under her magnolia trees.

Abigail caught me dreaming, primping the violets adorning her hair. Her elegance reminded me of the mistress I left behind; the teacher who taught me grace and opened my mind to learning, the mama I dreamed raised me. I gulped the sadness knotted in my throat.

“Mommy, I know Essie has a story. It dances inside her eyes when she looks at her flower.” Wren waited, twisting in her pink dress, primed for a twirl.

“A rose,” I said. “This is a very special rose.” I enticed Wren further.

Defeated, Abigail sat in the empty seat in front of us. “I have postcards to write. I brought your blanket, Wren. Winter arrives early this year.”

To my surprise Wren, squirming to sit in my lap, sat next to me waiting for a story, reminding me so much of little Evie tears watered in my eyes. “You are a beautiful girl,” I said. “As pretty as my rose.”

“Why do you carry it?” Wren’s tiny hand clutched my arm.

I hadn’t felt the pleasure and joy of innocence rising in my heart for a long time. “I grow roses. This rose is for a special woman.”

“Your mama?”

Wren’s question surprised me. I bit my lip, stretching for an answer. “Perhaps.”

“We have a gardener who grows roses that look like peppermint sticks.”

“A Village Maid rose.” I closed my eyes, inhaling the imaged candied fragrance.

“What is your rose called?” Wren tugged at my sleeve, waking me.

“It has no name yet, for I created it.”

“Doesn’t God create roses?”

“Oh, yes.” Wren walked her fingers down my arm, swirling the pearl buttons on my sleeve. She lifted the cuff and found the daisy-chain bracelet, a parting gift from a student. Her curious eyes passed over the thick purple scar curled across my wrist and forearm. I felt uneasy at her instant attachment. I slipped the daisies on her wrist, settling her fidgeting fingers as Katie used to do with mine. “God gives us wisdom to fashion our own, but it takes patience.” I tapped her nose, making her giggle. “People learn about flowers to cultivate new varieties to enjoy.”

“Like Mama having babies.”

“Wren.” Her mother snapped around. We exchanged a look, stifling a chuckle. Wren sat taller and held her finger to her lips to quiet her mama. Abigail handed me a throw for Wren and returned to writing her postcards. Wren snuggled under her blanket, ready for a story.

“But now,” I whispered. “It is time to tuck my rose away to sleep.”

“Essie, I wonder, do flowers dream?”

I sighed as her blanket stretched across our laps.

Passengers filed in; the train would soon leave the station. Wren’s eager eyes never left mine, even after the sellers of newspapers and snacks sang their offerings, racing up and down the aisle. I hurried to think of a fable. “Long ago, in a magical forest, a young prince set out to find a special gift for his new bride. He passed a well of diamonds.”

Wren gasped. “Diamonds are a brilliant gift.”

“‘The diamonds sparkle,’ said the prince. ‘But so does my bride.’ The prince marched on until he passed a field of gold grass he could pluck and pay for anything he wished.”

“Gold grass is a priceless gift,” Wren whispered.

“‘No,’ said the prince. ‘For my bride is priceless.’ The prince came to a meadow. Tired, he planted himself in the shade by a sapling. ‘You need the sun,’ said the prince. ‘And water.’ The prince plucked the tree from the shade, planted it in the sun, and watered its roots. Out of the corner of his eye, he spotted a glorious white rose, its petals sparkled gold and crimson. But how could he think of cutting it, for it was the only one in the valley?”

Wren nestled closer, her eyelids drooping. Abigail had turned around to listen.

“An old woman passed by and informed the prince the rose was hers; she planted it for her husband gone these many years. The woman, seeing the prince had cared for the tree, said, ‘I will gift you my rose, for you saved the tree my husband planted for me. This rose will bring you happiness, but you must never give it away until you find one worthy who will care for it.’”

The train’s bell hastened my story. “The woman dug up the rose, and before their eyes, the wondrous flower closed for its journey to the prince’s garden. When the prince’s new bride saw the rose, her eyes watered with joy. ‘You have gifted me the rose my father planted for my mother. We quarreled years ago. I was a stubborn child not to return and ask for forgiveness. You have brought me more than a gift, you brought me love.’”

Wren applauded, bouncing in her seat.

“More than diamonds or gold is the love of our parents. Some know not or treasure this love. Others embrace and remember. Always remember, Wren, a mother’s love is as sweet as a priceless rose.”

“Thank you,” Abigail whispered, taking her sleepy daughter. “Come, Wren, to our seat.”

Wren begged her mother to stay. “We’re going to Mobile to find me a sister.”

My tired eyes widened. “Excuse me?”

“Three years ago,” Abigail whispered as the conductor walked her daughter to her seat. She motioned to the conductor to wait and turned to me with a nervous grin. “We lost my eldest son in the war. I return home to Mobile. My husband stays behind on business in New York at his parents’ home.”

“North and South fighting each other.” I sighed.

“That was always the saddest part. My husband, Reginald, makes his way in politics. We’re looking to adopt. You travel south to speak?”

“To go home. We know many in Mobile.” I crinkled the kerchief hidden in my pocket, hoping for a rescue now.

“We?”

“The family who raised me.”

“I see.” Abigail bid a final wave to her husband. “We’re off. Please call on us should you visit Mobile. We are staying until Christmas. Wren would love to hear more of your stories.”

“I would like that.”

She shook my hand to the stares of the passengers now. “In my travels, I have learned one may find a treasured friend during chitchat on a train. I am thrilled I recognized you.”

“So am I.” I handed her the peppermint sticks I bought for Evie. “They'll settle Wren’s stomach for the journey. I noticed her rubbing her belly while I told the fable.”

“And my daughter’s green complexion.” She laughed. “Wren drank too much . . .”

“Orangeade.”

“Yes.”

“All aboard,” the conductor called.

“Thank you, Essie. Wren hasn’t been this happy in months. I hope you’ll visit us, dear.”

“I will try.” I cloaked my potted roses with gauze and cradled the seedlings in my lap.

“You should place your flowers back inside your box, miss,” the conductor said in passing. “Train’s about to leave the station.”

“Roses,” I whispered. At least the passengers aren’t staring at me, I thought.

They were.