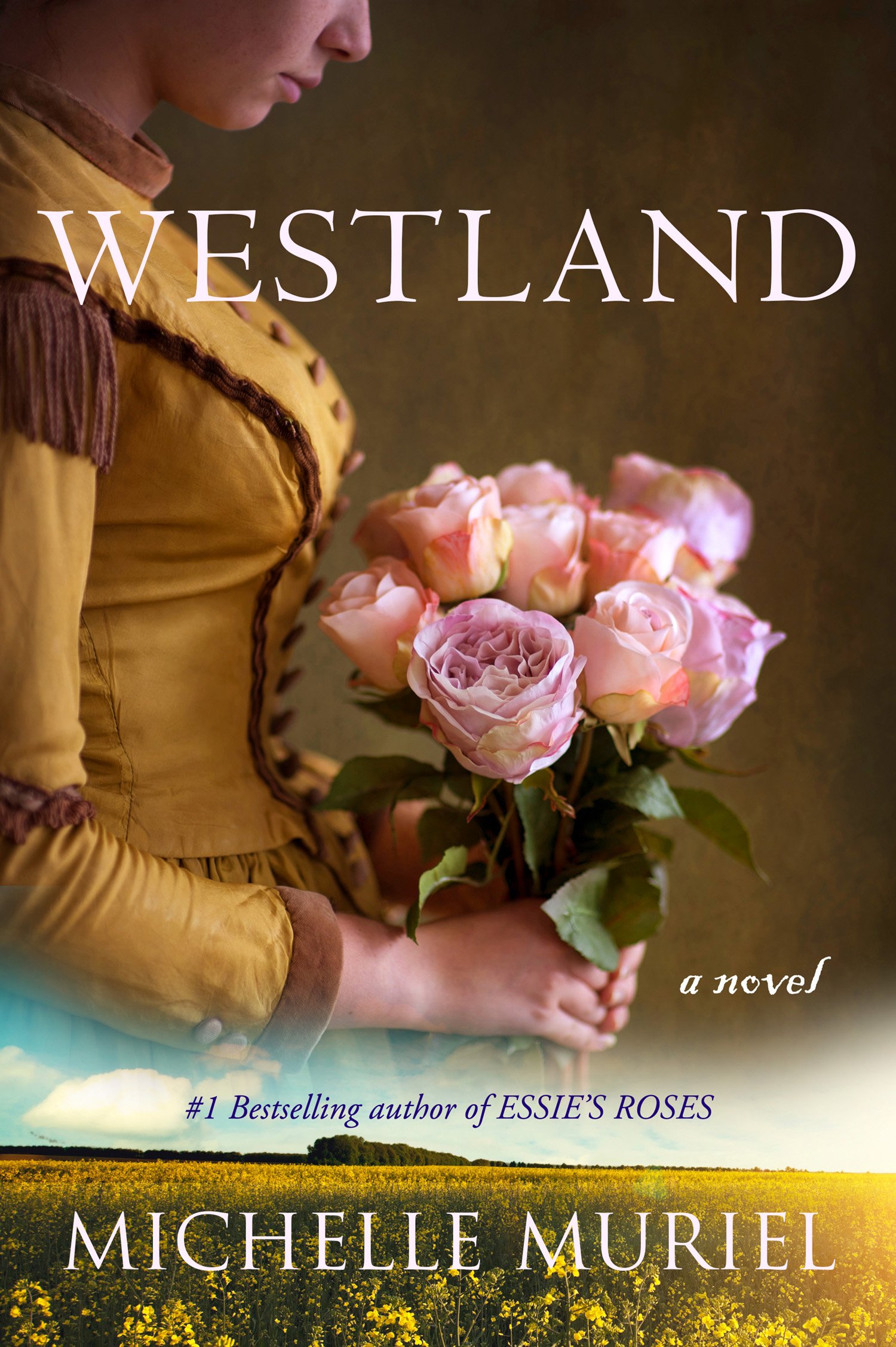

ESSIE'S ROSES by Michelle Muriel

EXCERPT

ESSIE'S ROSES by Michelle Muriel

Format: Hardcover, Paperback Book & eBook

Genre: Historical Fiction

ISBN: 978-0-9909383-0-9 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-0-9909383-2-3 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-0-9909383-1-6 (eBook)

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

PART I

Alabama, 1841-1854

* Prologue *

ESSIE MAE

The house appeared tucked in for the night. I snuck on the porch and up to the window near the front door for a better look. Delly would surely get me. Slave girl had no business spying on Miss Katie’s front porch, she’d say. But I knew Evie was in there, in that house, the little princess of this lonely plantation. To Evie and me, I wasn’t a slave, and she wasn’t a princess. We were just us. And I was gonna save her because she’d do the same for me.

The curtains were drawn, but I saw movement through a crack where the drape missed the edge of the window. Delly never closed the curtains because Miss Evie liked to watch the clouds. Evie taught me to see all kinds of wonders in those clouds, in secret. Though I knew dreaming in those white fluffs was mostly for white folks.

I saw him.

Massa Winthrop’s tailcoat brushed the curtain. Delly wasn’t there, nor Evie. Alone, he circled the foyer talking to himself, staggering, drinking his whiskey. The jagged bones in his hands and face revealed he hid a scrawny frame under his bulky clothes. Never saw Massa so thin. His silver-streaked hair appeared white in the dimness of a flickering light. Still no mustache or beard grew, though he scratched his chin like he had one. This proud sir that once strutted about Westland in fine pinstripes, silk ties, and outlandish hats, now paced the floor like a caged rat.

The windows were locked. Miss Katie never had Delly lock the windows, but Miss Katie was gone. She mustn’t know Mr. Winthrop come back. She’d run him off for sure. He wasn’t to come around Westland no more.

I crept away to look up at Evie’s bedroom window. No lights shone through her curtains. She always had them open. Evie would have wanted to lose herself in the stars tonight.

When I tiptoed back on the porch, his shadow paused in front of the window. He felt me, I knew. When his back turned toward me, I ducked. With a glimpse of his claw reaching for the curtain, I hit the floor.

My hand scraped a splintered slat. The sting tempted me to pull out the wood chip I knew pierced it. I didn’t move. Jesus, don’t let that man look down. The window slid open as I prayed it. "You best be careful, you Isabel ghost," he called out toward the yard, presuming I ran away. "I ain’t afraid of you!" A cough interrupted his howl.

I pressed my cheek into the cold wood, feeling another splinter pinch. Soon cedar overtook the musty smell. The cool air nipped the sweat on my forehead, sending a chill through my body. Evie would have said it was the devil laughing at us, reminding us he’s here.

Mr. Winthrop finally shut the window, but I dare not move. I took my mind someplace else, as Evie would have instructed. I imagined the smell of cloves, cinnamon, and vanilla and breathed them in. "Yes, Essie Mae," Evie whispered in my thoughts. "Think of the best things in the world. Make them so real. Then you won’t be scared. Then you can do anything."

I closed my eyes tighter, hearing Delly’s groan, "Ain’t got no time to be making this gingy cake for you, Miss Katie."

"Oh, Delly, I need a comforting snack," Miss Katie would say. "You make the best gingerbread in Alabama."

Quiet.

Nothing but crickets and frog songs now. I lay still, waiting, wishing we were all together. Laughing, eating Delly’s gingerbread with Evie and her mama Miss Katie.

I missed Evie, the way she would be scolding me right now for dreaming about ham and johnnycakes instead of setting my mind to the business at hand. Massa stole Evie. He held her, and despite Bo’s warnings, I would wait patiently for my chance to rescue her.

Seemed like hours since Massa walked around, disappeared, walked some more. Moon shown now. Cool breeze. With my cheek stuck between the slats of two dirty deck boards, my eyes rolled and turned without permission. Soon my lids tucked them in like a warm blanket.

Mr. Winthrop snapped them awake.

He cracked the window open and walked upstairs. The house finally slept. I waited. The soft wind, smell of imagined gingerbread, all against me.

I couldn’t concentrate as Evie often complained. I’ll try harder.

"Close your eyes to listen, Essie Mae," I heard Evie whisper in my thoughts. An owl stirred mischief. I’m tempted to search for it, name it. Evie’s gentle, small hand would discipline me to rest in the joy of his song. A nearby wind chime grabs my attention. The rustle of the cotton fields and the tree’s airy applause soon join them. The coolness of the damp cedar, my pillow for the night. I breathe in the promise of my dream and slowly exhale my release. In my thoughts, Evie conjures up scenes of joyful days at Westland, and I am there with her.

* 1 *

ESSIE MAE

A tattered gardening glove lay beneath Miss Katie’s favorite rosebush. It would be hard for her to love it again. Though, magically, those things we once loved that become tainted often find their way back into our hearts. While nature whispered its secrets in the warm night air, my mother lay in the barn giving birth to me.

I was born a slave on a small plantation in Alabama in 1841.

"The cotton field be blazing with a wild fire that night," Delly said. "Come evening, that devil’s flame sparking off colors like Miss Katie’s sunset sky, a creamy glow of orange and red. God be painting with the sun again, a crying, filling that sky with His crimson red like He went on poke His finger with a sharp stick and start drawing them lines in His sky. A soft breeze whispers . . ."

. . . the dreams and possibilities of a little girl’s spirit, but in its whisper, a haunting groan intruded, revealing the heartache of the night. The air: intoxicating, filled with the sweet aroma of treasured roses and imagined holy fragrances sending an invitation to fill the lungs with its heavenly scent until the smoky ash from the burning cotton fields perverted its perfect smell.

It always sounded so magical when Delly told me this story. Old Bo was sure to shoo away any of her embellishments. "That devil sky painted like a harlot’s dirty lips," he moaned. "Ain’t no soft breeze blowing nothing that night."

"Don’t you go listen to no slave who got no dreaming," Delly said. "Bo, you got no dreaming. Guessing you’s a ghost in the night cause you be dead."

Bo didn’t take to dreaming. "This world ain’t filled with all that sweet mess and make-believes, Essie Mae," he would say. "And it ain’t gonna give ya no favors. Bes get used to that."

Yes, I liked Delly’s stories best, especially the ones about my mama, Isabel.

At times, I could almost picture my mama. How she must have looked after tending Miss Katie’s garden, proud, standing with multi-colored blooms in her hands. The way she walked. Delly told me when Isabel walked; she glided like white folks, tall and straight, and wore ragged cotton dresses like they were fancy French gowns.

"Isabel talk so soft and sweet," Bo would say. "And she likes the mischief, jus like you, child." Delly added.

When I found myself wandering in the stillness of a dewy morning, soon standing under Miss Katie’s sweet magnolia trees, I wondered if my mama hid here. Mama, did you spy on Miss Katie and steal lemony blossoms too?

My mother was a ghost to me, I to this plantation. From my earliest memory, when Mr. Winthrop came near the barn, or I heard his footsteps near the slave quarters, no matter where I was, Bo’s hands snatched me up and whisked me to this quiet spot. Why would anyone ever think to look near the Winthrop home for this forgotten slave girl?

Bo said it was our hiding game. A game we played until Mr. Winthrop began his travels away from Westland. I knew it was to keep Mr. Winthrop from discovering me . . . from killing me. Bo wouldn’t want me to know, but I did.

Bo wasn’t my real daddy. I never knew or asked about him. An ugly heaviness told me never to ask. When I was old enough, Bo and Delly told me my mama, Isabel, was raped by a crazy runaway slave. Bo said they shot my no-good daddy near Sweet Water. "Bo woulda killed him," Delly said. Maybe he did.

My mama died giving birth to me. I didn’t want to think on a dead mama and a dead father, so I hid under Miss Katie’s magnolia trees to dream beautiful things about Isabel. Then maybe it wouldn’t be real. Maybe she wasn’t a slave; maybe I wasn’t one either.

Delly took my mama’s place but said it was Bo who raised me. Bo rarely talked. He towered above most men with an overwhelming presence, which is why I suspect Mr. Winthrop never bothered him much. He could do the work of ten slaves. His strong arms, weathered by the earmarks of a slave. Lashes and cuts decorated his back and shoulders. He did his best to keep me from their sight. I believe Bo loved my mama. When he talks about her, his eyes become soft, but he wouldn’t dare speak of such things.

Bo says I get my sass from Delly. Delly was Miss Katie’s house slave since Miss Katie was a girl. I longed for stories about my mother, but Delly mostly repeated the ones about how she looked when she was young. I could never picture Delly without her comforting belly, covered with a crisp white apron every morning, or her dainty wrists sewing my dresses. Delly’s firm hands, thick arms, and full cheeks were home.

The Winthrop plantation was grand, not extravagant as most. Westland, as it was called. It boasted a large, white two-story house at its entrance. There was a small henhouse, smokehouse, a large stable, carriage house, and a newly built barn Delly said Mr. Winthrop was particularly proud of, as it was of his design and construction.

Bo said, compared to the McCafferty’s, the slave quarters were better than most, but still an unwelcome home. Mr. Winthrop had no interest in improving them. A newer cabin stood nearby, my home. Too grand for a slave, but Miss Katie insisted.

"Child, the year you be born Miss Katie don’t sell a lick a cotton," Delly said. Scaled down to fit her means, Miss Katie would say. It may have been her way to keep the slaves she grew to love here long after her father’s days of high production. Many of them worked the plantation her father built; now it was all hers.

Although Miss Katie was the true owner of everything on the plantation, including the slaves, she gave leadership to her husband, Mr. John Winthrop, master of the house, as she claimed it should be. He didn’t deserve it. Delly wailed every night at supper, "Miss Katie ain’t never cross Massa Winthrop. This man be a fragile baby child, and Miss Katie take care a him cause all them folks jus laugh at him."

What Miss Katie did mind was everything that had to do with Westland’s upkeep and appearance. "It is not a matter of pride. It is a matter of honor," she declared. "What God gives you, you take care of. What a father leaves you, you honor."

Two magnolia trees stood in a cove at the right of the house. A small stone bench positioned underneath. A round table and two rockers sat on the front porch. They always seemed inviting. I was never to go near them. I wasn’t welcome at the Winthrop home and viewed from afar.

A vast array of notable trees towered over Miss Katie’s favorite places. A path lined with buttercups and wild violets curved its way up to the house. Vibrant hydrangea bushes bordered the porch steps, greeting each visitor with their color and honey fragrance. She would have it no other way.

With no mama of my own to worship, Miss Katie captivated me. After Miss Katie’s parents passed, she was the first woman who owned a plantation in these parts ever to be heard. Because of who her daddy and mama were, no one bothered Miss Katie’s Westland. Miss Katie was also the first woman near Sweet Water to have all the learning she did. Sometimes I would spy Miss Katie teaching the slaves reading and writing. It was illegal for a slave to learn to read, but I dreamed Miss Katie would teach me someday. It was a far off hope, but I dreamed it anyway.

Through her upstairs window, I often caught Miss Katie fussing about in her room. Frequently, I spotted her arranging flowers in a vase next to her window. She was particularly fond of roses.

"No one, not even Massa Winthrop be touching Miss Katie’s rosebushes, excepting you mama Isabel," Delly said.

Roses bloomed everywhere. One of my favorite sites: a white towering trellis housing pink roses that climbed and entangled themselves in the tiny windows. Bo built it for Miss Katie as a gift, and it was pure jubilation for Delly when Mr. Winthrop burned jealous at the sight of it.

Another trellis, an archway, marked the entrance to Miss Katie’s secret garden. Two weeping willows introduced a path paved with river rocks leading the way to its tall gate. Over the years, the prehistoric trees draped a curtain hiding the path. Delly revealed the willows were Miss Katie’s purposed deterrence from unwanted visitors. They never allowed me inside, but I spied through the slats when Delly went in to cut Miss Katie fresh flowers. No one could keep me from savoring its sweet smell. It traveled freely through the air at Westland for all to enjoy.

Miss Katie’s favorite rosebush was one planted a good stone’s throw in front of the house. I suspected so she could keep a close eye on it, though she declared otherwise. "I love to watch them grow there," she said. I never knew exactly why she loved it so. Delly bragged, "That rosebush smell sweeter than all the buds Miss Katie grow in her garden. You mama had the gift. Sure did."

Growing up, I doubt a day went by when Delly wouldn’t tell me, "You’re too smart for your own good." Sometimes she said it as a warning, most of the time she said it in awe. Things just came to me, even without learning from any books. I wanted to learn about everything. As I grew older, that part of my personality became a challenge for Bo and Delly to rein in. But one thing I learned: I wasn’t the only ghost on this plantation. There were others.

Sometimes I caught glimpses of the ruffles and dainty things of a beautiful Southern little girl: white gloves, petticoats, bright-colored bonnets, and buckled shoes. Bo and Delly tried to convince me otherwise. For years, they told me ghost stories about a white girl who wandered the cotton fields at Westland.

"Skin light as milk," Delly whispered.

"Eyes black as night," Bo growled.

"Running through the grasses and the fields to gives a child a fright," they warned, proud of their haunting fable because it kept me away from the Winthrop house, at least for a while. I wasn’t allowed to play too far away from the plantation—not until I was six—when my real adventures began. One day it finally happened. I saw her.

The first morning Mr. Winthrop was away, I snuck outside to the back of the house to play. A mulberry tree tempted me. After I had my fill, I took to my spying game. Suddenly, I didn’t feel like a peek in the Winthrop home. My stomach cramped, the effects of my morning gorge. As I walked near the magnolia trees to rest myself, there she was, sitting on Miss Katie’s lap on that perfect stone bench underneath the trees.

Evie was stunning.

She had golden hair like Miss Katie. I was fixated on the lightest strands near her face. It appeared some of the white from her skin found its way to mingle throughout her hair. How did God do that? The sun kissed her cheeks to a bright pink. Soon Miss Katie opened a sky-blue parasol to shade Evie from the sun. I had never seen a white girl before, but if I had, I knew Evie would stand apart among them. She shone like a sunflower, wearing the prettiest yellow dress decorated with tiny white flowers that only brought out her sunlit hair even more.

Miss Katie held a bonnet I imagined Evie protested wearing. Every time Evie stretched her face toward the sun, Miss Katie shaded her face. And every time, Evie moved her mother’s hand away to soak in the light. What I remember most about Evie that first day: her hair and face shone brighter than the sun. When I moved in closer to get my private stares in, it happened.

Evie saw me.

My heart raced faster than the day Delly caught me staring in the Winthrop’s front porch window. I ducked behind a pine tree and froze. Though my heart pounded, I wanted to look back at the little girl with the sunbeams in her hair. Footsteps interrupted.

Snapping twigs.

Crunching leaves.

The sounds thundered closer.

Convinced it was Miss Katie, I panicked. What would I say? I exhaled, snatching another breath of air. Delly’ll get me good. Turning off my thoughts, I tightened my lips, covered my eyes, and prayed to God to make me invisible or make Miss Katie go away; either deliverance suited me.

After a few seconds, I opened my eyes to see if the good Lord heard my prayer. He answered in his own way. There she stood. Not Miss Katie—Evie.

Then that white girl did a strange thing—she held my hand. Evie put her finger to her mouth, motioning for me to be quiet. I looked out from behind the tree to where Miss Katie sat. She was busy talking with a visiting neighbor, distracted by the woman’s basket of eggs. I trembled. I never held a white girl’s hand before, but Evie wouldn’t let mine go.

How soft it was. I cringed, embarrassed at my own sticky hand. Evie only held mine tighter when she felt it squirming. She stood there smiling at me, swaying to her own music, looking into my eyes as if watching her tiny reflection swirl inside the colors. After a moment, she pulled a ribbon from her hair and passed it to me in secret. She slid her hand out from mine and ran back to her mother.

I didn’t move.

I stood staring at Evie as she peered out from her mother’s dress back to look at me. Miss Katie picked her up. I hid behind the tree. The woman with the eggs was leaving now. Miss Katie turned to take Evie back into the house. I looked around the tree to get one last glimpse, and Evie smiled, managing a secret wave goodbye.

I bolted back to the slave quarters, shut the door and giggled. I hid my yellow ribbon, replaying our meeting over and over again. I couldn’t stop smiling. I finally saw her, and she was beautiful.

I didn’t know how much longer Bo and Delly thought they could deceive me, but I understood it was to protect me from Mr. Winthrop. Over the years, we did not see Mr. Winthrop around Westland much. Evie and I welcomed his absences as treasured opportunities to meet in secret.

I was excited to turn six. I knew it meant I was old enough to go beyond the plantation to at least the creek, a good half-mile or so away. It kept me out of Bo and Delly’s hair for the day. With Mr. Winthrop traveling more, they gave me room to do as I please, my hiding game with Bo at last over.

Evie was a dreamer. She couldn’t help shining a zest for life. Dreaming. That was her gift. Evie could think up a dream a second, and if you couldn’t, she thought one up for you. Even though I was still afraid strange Mr. Winthrop might find and kill me in the night, Evie’s persuasive pleading convinced me I would miss out on the adventure of a lifetime. But we were already secretly off on our own adventures together since that first day. The place of escape: our hillside.

It overlooked the meadow with its misty peaks and valleys promising years of discoveries and daydreams. The lime-green grass rolled over the surrounding hills displaying patches of thickets, straw, and wildflowers, lying perfectly like one of Delly’s quilts arranged meticulously on my bed. At the slave quarters, my view was the dirt and overgrowth of the unattended cotton fields Miss Katie no longer cultivated—dead things, but our hillside showed an abundance of life.

No one bothered us here, and no one knew about this place but us. When we lay down on that perfect grass and looked up at the sky, the clouds seemed too close to us, floating and fighting for position above our heads. We became lost in those clouds and the stars that outnumbered even Evie’s dreams. No other place would do.

Our hillside also overlooked the Alabama plantation we knew, but when we came here, we never faced it. We lay upon our grass of freedom away from that plantation, looking up at the endless possibilities of the morning and evening skies, resting among the clouds, imagining inside the stars. Our destiny was not focused on our birthplace but on the horizon where our dreams would lead us to the freedom we both longed for. It was our place, our sanctuary, our secret.